Astronomers have long debated why so many icy objects in the outer solar system look like snowmen.

Now, thanks to a new computer simulation in a research paper published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Michigan State University (MSU) researchers have evidence of the surprisingly simple process that could be responsible for their creation.

Far beyond the violent, chaotic asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter lies what is known as the Kuiper belt. There, past Neptune, are icy, untouched building blocks from the dawn of the solar system, known as planetesimals.

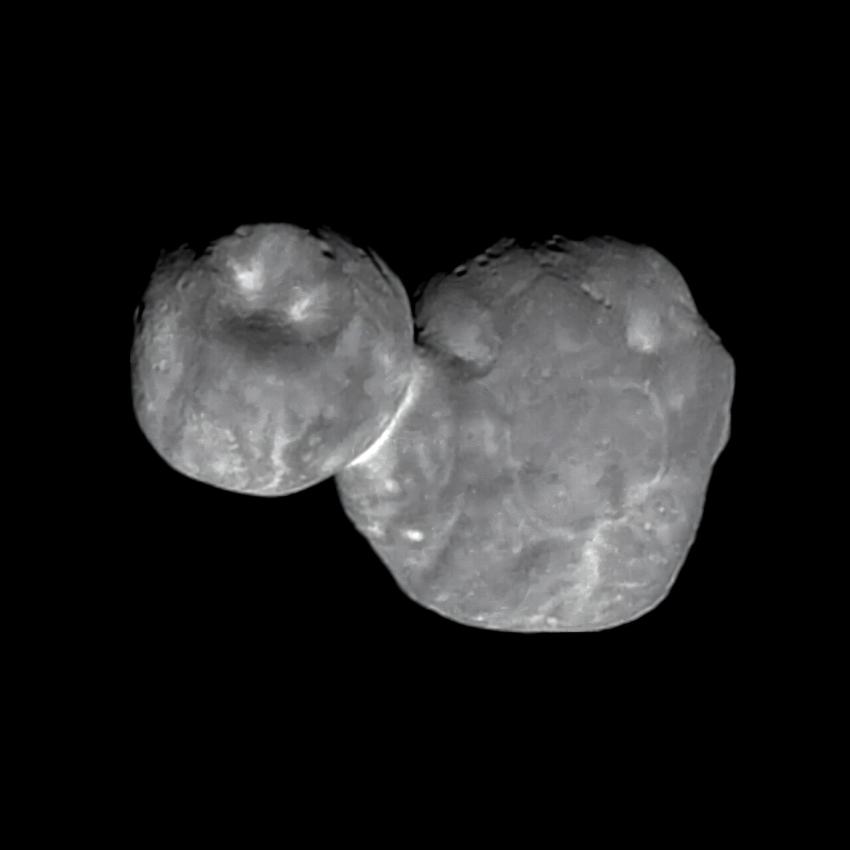

About one in 10 of these objects are contact binaries, planetesimals that are shaped like two connected spheres – much like a snowman – including the most distant and most primitive object ever explored by a spacecraft, the ultra-red, 4 billion-year-old body known as Arrokoth, which was discovered in 2014 by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft.

But just how objects such as Arrokoth came to be has long been a mystery.

Jackson Barnes, an MSU graduate student, has created the first simulation that reproduces the two-lobed shape naturally with gravitational collapse.

Earlier computational models treated colliding objects as fluid blobs that merged into spheres, making it impossible to form these unique shapes.

But with the help of MSU’s Institute for Cyber-Enabled Research (ICER) and its high-performance computing cluster, Barnes says his simulations produce a more realistic environment that allows objects to retain their strength and rest against one another.

Other formation theories involve special events or exotic phenomena that, while possible, aren’t likely to happen on a regular basis.

“If we think 10 per cent of planetesimal objects are contact binaries, the process that forms them can’t be rare,” said Earth and Environmental Science Professor Seth Jacobson, senior author on the paper. “Gravitational collapse fits nicely with what we’ve observed.”

Contact binaries were first imaged up close by the New Horizons spacecraft in January 2019. These images prompted scientists to take another look at other objects in the Kuiper belt, and it turned out that contact binaries accounted for about one in 10 of all planetesimals.

These distant objects float mostly undisturbed and safe from collisions in the sparsely populated Kuiper belt.

In the early days of the Milky Way, the galaxy was a disc of dust and gas. Remnants of the galaxy’s formation are found in the Kuiper belt, including dwarf planets such as Pluto, comets and planetesimals.

Planetesimals are the first large planetary objects to form from the disc of dust and pebbles. Much like individual snowflakes that are packed into a snowball, these first planetesimals are aggregates of pebble-sized objects pulled together by gravity from a cloud of tiny materials.

Occasionally as the cloud rotates, it falls inward on itself, ripping the object apart and forming two separate planetesimals that orbit one another.

Astronomers observe many binary planetesimals in the Kuiper belt. In Barnes’ simulation, the orbits of these objects spiral inward until the two gently make contact and fuse together while still maintaining their round shapes.

How do these two objects stay together throughout the history of the solar system? Barnes explains they’re simply unlikely to crash into another object. Without a collision, there’s nothing to break them apart. Most binaries aren’t even pocked with craters.

Scientists long suspected that gravitational collapse was responsible for forming these objects, but they couldn’t fully test the idea. Barnes’ model is the first to include the physics needed to reproduce contact binaries.

“We’re able to test this hypothesis for the first time in a legitimate way,” Barnes said. “That’s what’s so exciting about this paper.”

Barnes expects his model will help scientists understand binary systems of three or more objects. The team is also working to create a new simulation that better models the collapse process.

ENDS

Media contacts

Sam Tonkin

Royal Astronomical Society

Mob: +44 (0)7802 877 700

Science contacts

Jackson Barnes

Michigan State University

Professor Seth Jacobson

Michigan State University

Images & captions

Caption:This image was taken by NASA's New Horizons spacecraft on 1 January 2019 during a flyby of Kuiper belt object 2014 MU69, known as Arrokoth. It is the clearest view yet of this remarkable, ancient object in the far reaches of the solar system – and the first small "KBO" ever explored by a spacecraft.

Credit: NASA

Further information

The paper 'Direct contact binary planetesimal formation from gravitational collapse' by J. Barnes et al. has been published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stag002.

Notes for editors

About the Royal Astronomical Society

The Royal Astronomical Society (RAS), founded in 1820, encourages and promotes the study of astronomy, solar-system science, geophysics and closely related branches of science.

The RAS organises scientific meetings, publishes international research and review journals, recognises outstanding achievements by the award of medals and prizes, maintains an extensive library, supports education through grants and outreach activities and represents UK astronomy nationally and internationally. Its more than 4,000 members (Fellows), a third based overseas, include scientific researchers in universities, observatories and laboratories as well as historians of astronomy and others.

The RAS accepts papers for its journals based on the principle of peer review, in which fellow experts on the editorial boards accept the paper as worth considering. The Society issues press releases based on a similar principle, but the organisations and scientists concerned have overall responsibility for their content.

Keep up with the RAS on Instagram, Bluesky, LinkedIn, Facebook and YouTube.

Download the RAS Supermassive podcast